EDITOR’S NOTE: As our state and nation continue to confront the COVID-19 pandemic, state fiscal and federal policies will play key roles in ensuring the physical and economic health of Nebraska and its residents. OpenSky Policy Institute staff will be continuously analyzing state and federal policies that impact Nebraskans during this national emergency. This analysis is part of that effort. You can access more of our pandemic-response policy analysis here. We also remind you that OpenSky staff are working remotely during the pandemic response. Remote contact information for staff members can be found here.

While racial unrest persists throughout Nebraska and the nation, the COVID-19 crisis continues to disproportionately harm people of color. There are more than 2.6 million cases of novel coronavirus in the U.S. alone, with more than 125,000 deaths,[1] and ample evidence shows that nonwhite people are becoming infected with, and dying from, COVID-19 at a disproportionately high rate.

Nebraska’s Department of Health and Human Services published statewide data on race and ethnicity on June 30, becoming the 49th state to do so.[2] Both the statewide numbers and data from Douglas County show unequal infection rates across racial and ethnic groups. These groups make up an outsized portion of frontline workers in the state, meaning they have generally higher rates of exposure while working to keep our economy and society afloat.

Minority communities hit hardest nationwide and in Nebraska

The mortality rate for Black Americans is 2.3 times higher than the mortality rate of whites and Asians, twice as high as the mortality rate of Latinos, and 1.5 times as high as the Indigenous mortality rate, according to aggregated national data.[3] Collectively, Black Americans represent 13% of the Americans residing in areas that are releasing COVID-19 mortality rate by race, yet make up 27.5% of cases[4] and have suffered 27% of the COVID-19 related deaths in those areas.[5] These discrepancies in confirmed cases and mortality rates indicate structural inequities and inadequate public health support for Black populations.

Nebraska was one of the last states to announce it would track COVID-19 numbers by race and ethnicity and has a sizable amount of uncertainty in its reporting, with roughly 14% of cases reporting no racial or ethnic identity.[6] However, the data on cases where racial and ethnic identity was reported clearly shows an outsized impact on Nebraskans of color. Non-white Nebraskans make up just 22% of the state’s population but acount for nearly 70% of COVID cases, 58% of hospitalizations and 37% of deaths.[7] The greatest disparities are for Latinx Nebraskans, who compose roughly 11% of the state’s population, but account for 58.6% of cases and 26.3% of deaths out of the cases where ethnicity is known.[8]

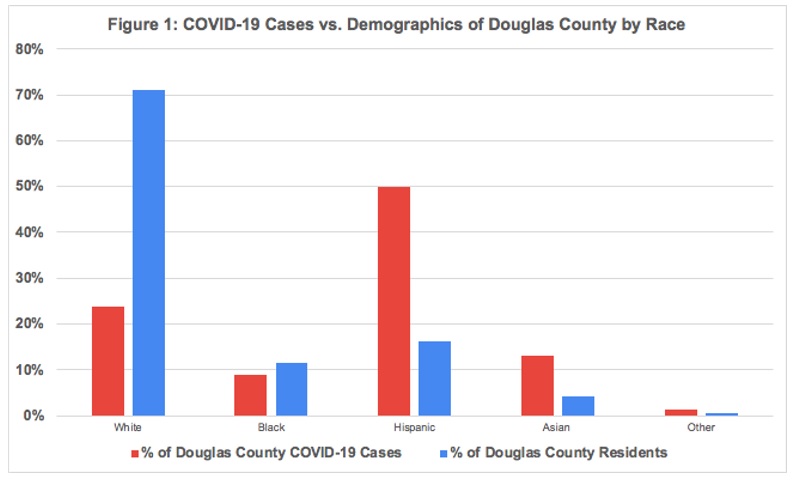

Data for Douglas County, which has been tracking race and ethnicity for longer and has more complete data, also shows a disproportionate impact, with people of color accounting for more than 76% of confirmed cases despite being only 29% of the Douglas County population.[9] A breakdown of confirmed cases by race compared to the county’s population demographics is shown in Figure 1.

Women and workers of color are overrepresented among Nebraska’s essential workers

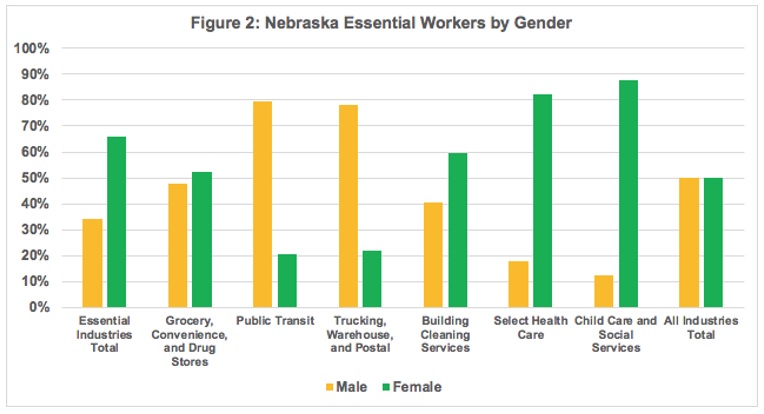

The disparity in infection rates is caused in part by high participation of people of color in frontline industries, like health care, grocery and food processing. Frontline workers are often in customer-facing positions that put them at high risk of infection or in positions so critical to ensuring access to basic necessities during the pandemic that they can’t stay home. For example, home health aides are vital to keeping many Nebraskans healthy, grocery workers are needed to ensure access to food, and janitorial and cleaning staff are necessary to clean spaces at risk of contamination. Frontline workers also are in the child care and social services industry, trucking and postal industries, and food processing and meat packing industries. More information on how the essential industries were selected for this brief is found in the methodology note at the end of this analysis while the numerical breakdown is shown in Figure 2.

Women are especially overrepresented among frontline workers in Nebraska: composing nearly 68% of essential workers while making up only 50% of the total workforce. This discrepancy is the largest in select health care (82% female) and child care and social services (88% female).

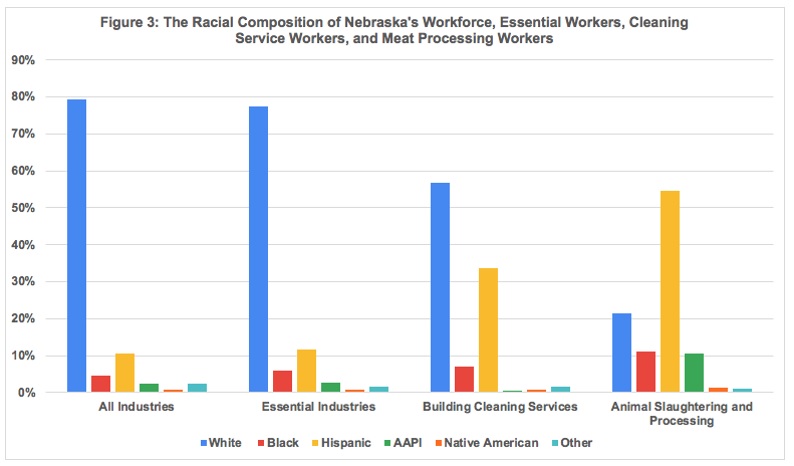

Frontline workers are also slightly more likely to be people of color, who make up 20.6% of the state workforce but 22.6% of the frontline workforce. The difference, however, is much more dramatic in some industries with a significant amount of exposure: building cleaning services and meat packing and slaughtering facilities. Workers of color are substantially overrepresented in these two industry groups. Specifically, Hispanic workers compose 33.6% of janitorial service workers and 54.5% of animal slaughtering and processing workers but make up only 10.7% of the total workforce. The racial demographics of Nebraska’s workforce, essential industries, cleaning services, and meat processing facilities are shown in Figure 3.

Policy steps can increase racial equity in COVID-19 outcomes

The first step we can take is to acknowledge the racial discrepancies among COVID-19 health outcomes and target resources and information to the most heavily affected populations. Steps are being taken in cities and states across the nation to address racial disparities in COVID-19 cases. States use race and ethnicity data in a variety of ways, including targeting and soliciting funding, tailoring stakeholder outreach and engagement, informing public health initiatives and strengthening governmental processes to better address disparities.

In Michigan, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer established a Coronavirus Task Force on Racial Disparities”[10] while Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot has partnered with state nonprofits to establish a Racial Equity Rapid Response Team to engage community members and conduct regional briefings.[11] Increasing community engagement and outreach can also assist states in non-COVID-19 initiatives, such as increasing health care access and equity, Medicaid managed care contact languages for social determinants of health, and workforce development strategies.[12]

In Nebraska, federal stimulus dollars provided through the Community CARES plan could be better targeted toward communities of color, as they have seen the greatest impact from the virus. The plan prioritizes funding for organizations that provide support to “underserved communities” and “higher-risk populations,” but there is no specific mention of communities of color in the DHHS guidance. As communities of color are both underserved and at-risk, they need to be a top priority in allocating plan resources.

The Legislature should pass LB 918, a bill creating a Commission on African American Affairs, to help policymakers assess the racial and ethnic impacts of policy changes. The new Commission, along with the Commission on Indian Affairs and the Commission on Latino-Americans, would be responsible for completing a disparity study in government contracting to be submitted to the Legislature every two years. Passing LB 918 would help the state collect new data in areas such as health, education, and transportation — acknowledging the vital importance of race-based data collection in policy decisions.

Finally, Nebraska should take concrete steps to support essential workers, preserving both their health and their economic security. Policymakers should consider increasing childcare subsidies in the case of any school closures in the fall, providing personal protective equipment and free testing to all essential workers, or enacting paid sick leave at the state level by passing LB 305, the Healthy and Safe Families and Workplaces Act. Through measures to support essential workers, Nebraska would be targeting assistance not only to a group that is more at risk of contracting COVID-19, but also a population where women and workers of color are disproportionately represented.

Conclusion

Nebraskans of color are bearing the brunt of the health impacts of the COVID-19 crisis as seen by disparities in infection and mortality rates and by their overrepresentation in frontline industries; however, those communities may not be receiving the support they need and the state may not be using its dollars as effectively as possible.

Methodology Note

The profile uses the most recent estimates of data from the American Community Survey, using a sample that includes data from five years, including 2014 to 2018. The “frontline” or “essential” industry groups, each of which includes one or more specific industries (as classified using the Census Bureau’s Industry Codes), are:

- Grocery, Convenience, and Drug Stores: Grocery and related product merchant wholesalers (4470), supermarkets and other grocery stores (4971), convenience stores (4972), pharmacies and drug stores (5070), and general merchandise stores, including warehouse clubs and supercenters (5391).

- Public Transit: Rail transportation (6080) and bus service and urban transit (6180).

- Trucking, Warehouse, and Postal Service: Truck transportation (6170), warehousing and storage (6390), and postal service (6370).

- Building Cleaning Services: Cleaning services to buildings and dwellings (7690).

- Health care: Offices of physicians (7970), outpatient care centers (8090), home health care services (8170), other health care services (8180), general medical and surgical hospitals, and specialty hospitals (8191), psychiatric and substance abuse hospitals (8192), nursing care facilities (skilled nursing facilities) (8270), and residential care facilities, except skilled nursing facilities (8290).

- Childcare and Social Services: Individual and family services (8370), community food and housing, and emergency services (8380), and child day care services (8470).

- Animal Slaughtering and Processing (1180)

OpenSky’s analysis includes all Nebraska workers in these essential industry categories, but no workers in essential occupations that are outside of these categories. As a result, the estimates exclude some workers in occupations (but not industries) that should clearly be considered part of this essential category, while also including some workers who are not in frontline occupations, even though they are in frontline industries. For example, a police officer is a frontline occupation in a non-frontline industry, while a school bus driver is a non-frontline occupation (at least in areas where schools are closed) in a frontline industry (public transit). Still, the vast majority of workers in the seven essential industries are essential workers.

Download a printable PDF of this analysis.