EDITOR’S NOTE: As our state and nation continue to confront the COVID-19 pandemic, state fiscal and federal policies will play key roles in ensuring the physical and economic health of Nebraska and its residents. OpenSky Policy Institute staff will be continuously analyzing state and federal policies that impact Nebraskans during this national emergency. This analysis is part of that effort. You can access more of our pandemic-response policy analysis here. We also remind you that OpenSky staff are working remotely during the pandemic response. Remote contact information for staff members can be found here.

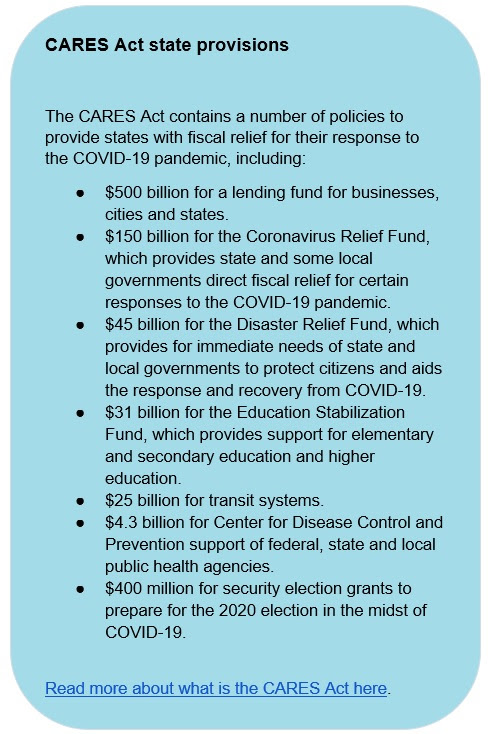

In recognition of the fiscal toll this all will have on states, the federal government put together a $2 trillion aid package, known as the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act), of which the state of Nebraska is expected to receive about $1.4 billion.[1] This equates to about 30% of Nebraska’s FY 21 general fund budget.[2] While this will help ease the fiscal burden, it’s also likely to be insufficient to offset the damage — the full magnitude of which we may not know for months or even years.

Economic impact will be massive, but exactly how large remains to be seen

State revenues will be impacted significantly by widespread pandemic-related shutdowns and job losses not only for the current year, but likely several years into the future. Nationally, Moody’s analytics estimates state revenues will decline by at least 10%, with most falling by 15% to 25%, even when accounting for the federal stimulus.[3] Under Moody’s best case scenario, Nebraska would see a roughly $500 million drop in receipts in FY 21 alone. As a result, state governors are asking for upwards of $500 billion in federal aid to states — on top of CARES Act funding — to help shore up state finances because of the impact of COVID-19.[4]

In a prior brief, we compared what a downturn in Nebraska similar to the Great Recession would look like today and the results were bleak, even with revenues decreasing less than 5% — well below Moody’s estimates for the current situation. National forecasters, however, have started to say that the pandemic could create a downturn that is much more significant than the Great Recession. Several models project that even with the CARES stimulus funds,[5] the U.S. economy could experience an annualized decline by as much as 40% in just the second quarter,[6] which would be the largest quarterly plunge since World War II.[7]

Unemployment claims likely to account for a lot of stimulus dollars

There will be a significant need for CARES Act dollars to shore up state institutions hit the hardest by the COVID-19 crisis, like unemployment insurance programs. Nebraska’s system is experiencing an unprecedented spike in claims: in just the first four weeks of the pandemic, nearly 84,000 Nebraskans filed for unemployment,[8] bringing total unemployment in Nebraska to an estimated 114,000 with an unemployment rate of nearly 11%.[9] The Economic Policy Institute has estimated unemployment in Nebraska will reach 15.1% in July, peaking at over 157,000 unemployed in the state.[10] For context, unemployment in the aftermath of the Great Recession peaked at 48,000 claims in January 2010.[11]

Nebraska is fortunate to have a well-funded unemployment trust fund, with $456 million at the start of 2020.[12] However, prior to the crisis, the state’s program was only reaching 10% of those eligible[13] and so the unprecedented spike in claims could easily overwhelm the fund.[14] At the fund’s balance at the beginning of 2020, it could only sustain maximum benefits for all currently unemployed Nebraskans and those who have applied in the wake of COVID-19 for just over 9 weeks, although it’s important to note that not all in Nebraska who have applied for UI earn enough to qualify for maximum benefits.[15] If, however, more workers become eligible for unemployment or the pandemic extends for several months or longer, as some experts have discussed, a considerable portion of CARES Act funding may be needed just to shore up our UI fund and help out-of-work Nebraskans survive the pandemic.

State savings account might not be sufficient to weather the pandemic

Adding to Nebraska’s precarious financial situation is a Cash Reserve Fund that is well below the recommended level. Going into FY 21 amidst the COVID-19 crisis, the fund will sit at just over 7% of revenues — less than half the 16% level recommended by the Legislative Fiscal Office — assuming no money is deposited into the fund this year as was originally projected.[16] If the state loses 10% of revenues in the remaining months of this fiscal year and 10% in the next, which would be reflective of Moody’s minimum projection, it would equate to roughly $592 million in revenue losses,[17] $220 million more than the projected $372 million Cash Reserve Fund balance for FY 21.[18] Given this, it’s not difficult to imagine a scenario in which the state’s current cash reserve proves insufficient to prevent cuts to services Nebraskans need amid the pandemic, or tax increases.

COVID-19 starting to impact other state services as well

Other institutions are already seeing the fiscal effects of COVID-19, including the University of Nebraska, which expects a $50 million shortfall.[19] The university system is expected to receive about $31.6 million in CARES funding through the Education Stabilization Fund, though half is required to be awarded to students for emergency financial aid grants.[20]

Hospitals are also facing existential threats, although not necessarily from being overwhelmed by COVID-19 patients. Instead, some hospitals are losing revenue as they cancel or postpone elective surgeries and outpatient services to free up beds and resources for a potential influx of COVID-19 patients.[21] A substantial amount of state and federal dollars may be needed to help our state’s hospitals weather the crisis.

History also has shown that enrollment in programs like Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) increase during economic downturns and so those programs are likely to see their resources strained, as well.[22] As such, a substantial investment of CARES Act funding may be required to provide needed support to Nebraskans through these programs, particularly if the pandemic carries on for several months or longer.

Conclusion

While the CARES Act will provide substantial and important support to Nebraska and other states during the pandemic, the needs created by COVID-19 are likely to exceed the aid provided in the CARES Act — and perhaps considerably so. The way state leaders make use of the federal aid we do receive will play a vital role in determining how well Nebraska and its residents weather this crisis.

Download a printable PDF of this analysis.