Policy brief: Rural Nebraskans pay more in combined property/income taxes

There is a common misconception that Nebraska’s farmers and ranchers pay little or no state income taxes, so it balances out the fact that they pay more in property taxes.

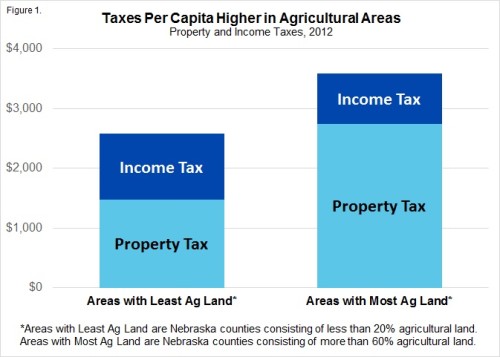

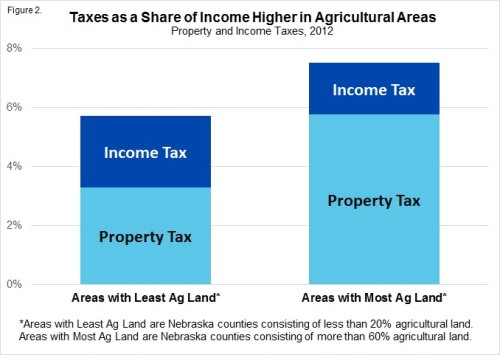

But a look at property and income taxes combined over the past several years shows the true picture: Nebraskans

in areas of the state that have high amounts of agricultural land (rural areas) paid more taxes — both on a per-capita basis and as a share of income — than people in areas that have the least agricultural land (urban areas).

in areas of the state that have high amounts of agricultural land (rural areas) paid more taxes — both on a per-capita basis and as a share of income — than people in areas that have the least agricultural land (urban areas).

Data are not available to directly compare taxes paid by farmers and ranchers to urban wage earners. But it is possible to compare taxes paid in urban and rural areas.

The data show that although income taxes paid in rural areas are lower, property taxes there are higher so that rural residents pay more when both taxes are combined.

It was once true that urban Nebraskans generally paid slightly more per person than rural Nebraskans, but this situation reversed around 2007.

By 2012, the last year for which such data are available, rural Nebraskans paid more than $1,000 more per person than their urban counterparts — a difference of nearly 40 percent (Figure 1).

Measured as a share of income rather than per-person, taxes also are higher in rural Nebraska (Figure 2).

Rising land values squeeze farmers and ranchers

The skyrocketing value of Nebraska’s farm and ranch land has contributed to this growing imbalance. From 2003 to 2012, agricultural land in Nebraska saw a 116 percent increase in value for tax purposes, while commercial and residential property each increased 45 percent.

Nebraska now relies on agricultural land for 26 percent of all property tax revenue – up from 19 percent in 2003. And while agriculture’s share of property taxes has increased in recent years, the state’s rural population has not grown.

The state has taken steps to relieve pressure on agricultural land owners – such as reducing the valuation of agricultural land for tax purposes to 75 percent of its market value since 2007. These efforts have not been as effective as intended, however, as agricultural property taxes have still risen steeply in recent years.

Furthermore, increases in the value of agricultural land have not necessarily translated into boosts in income for farmers and ranchers. In other words, their ground is worth more, but it does not necessarily generate more money.

Conclusion

Our current tax imbalance that has rural Nebraskans paying more in combined property and income taxes has caused problems regarding fiscal issues like school funding. Our agricultural producers have seen their share of our K-12 bill increase along with the rise in their property taxes.

If Nebraska heeds the calls of some and cuts income taxes, these fiscal issues and rural-urban tax disparities are likely to be exacerbated.

Download a printable PDF of this analysis.

Sources: Property tax data from Nebraska Department of Revenue Property Assessment Division; Population data from US Census Bureau; Personal Income data from US Bureau of Economic Analysis