Policy brief – LB 720 poised to be another costly incentive program

Tax incentives are aspects of a state’s tax code designed to encourage economic activity; however, there is little evidence that they have attracted enough investment in Nebraska to warrant the high cost. The ImagiNE Act (LB 720, with AM 1614), if enacted, would likely continue Nebraska’s tradition of costly and questionably effective tax incentive programs.

Nothing in LB 720 would prevent it from becoming another costly program

Tax incentives are a form of economic development policy wherein a government provides new or expanding businesses with tax credits or other financial benefits.[1] However, these programs aren’t shown to have a significant link to income levels or future economic growth and can result in states foregoing significant revenue without a corresponding benefit.[2]

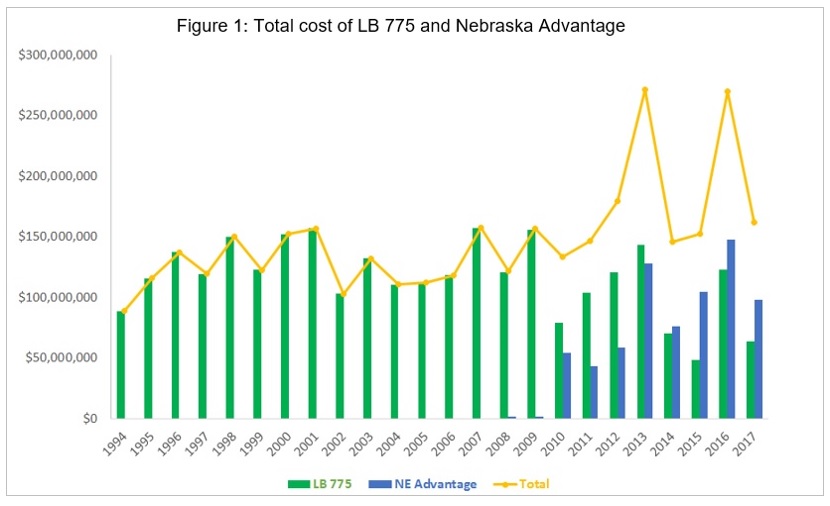

In Nebraska, that foregone revenue has added up significantly since the first incentive program, LB 775, was adopted in 1987 in order to keep ConAgra Brands Inc., from moving its headquarters (Figure 1).[3] There were nearly $300 million in LB 775 credits outstanding as of 2017 and the state is obligated to pay through 2025.[4] The Nebraska Advantage Act became the state’s second major incentives program when it was passed in 2005. By 2027, the Department of Revenue projects there will be more than $1.5 billion credits outstanding under this program.[5]

There were nearly $500 million credits outstanding as of 2017 and the state is obligated to pay through 2050.[6] There is no guarantee that the ImagiNE Act’s revenue losses won’t balloon similarly. It is projected to cost $30 million in fiscal year 2021 and grow to $197 million by fiscal year 2029, causing a total revenue loss of about a billion dollars, not including losses from property tax exemptions and lost local option sales tax revenue.[7] Additionally, it’s designed to ramp up quickly, so the state could end up paying out credits for all three programs in the same year.

Little correlation to economic growth

Business tax breaks like those in the current Nebraska Advantage program and proposed in the ImagiNE Act have little correlation with employment or future economic growth, according to Dr. Timothy Bartik of the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. Bartik estimates that, nationally, incentives impacted the location decisions of between 2% to 25% of firms — meaning that at least 75% of firms receiving incentives would have made the same location, expansion and retention decisions regardless of incentives. Overly investing in ineffective tax breaks pull revenue away from services like education and job training, which Bartik says can be more cost-effective than tax breaks in encouraging local job growth.[8] Public school investments — or a lack thereof — can impact wage growth over time and Bartik has found that “incentives financed by cuts in public schools reduce per-capita income of state residents by over 4%.”[9]

Nebraska’s incentives are generous and not targeted

Nebraska has a more costly incentive program than most other states, ranking as high as fifth nationally in one measure of tax incentive volume in a national report by Bartik.[10] The state’s business taxes are average, but its incentives are 80% more generous than the national average, Bartik said. This session, lawmakers are considering enacting not only another expensive incentive program, but some are also contemplating a cut in the top corporate tax rate. The combination of revenue lost due to the combination of the ImagiNE Act and a corporate rate cut would significantly harm programs that are actually proven to drive economic growth, such as K-12 and higher education.

ImagiNE Act does not adequately incentivize high-wage jobs

Annual pay in Nebraska is 21% below the national average, especially outside the Omaha area, according to a 2016 study done for the governor by SRI International. The state’s incentives programs have failed to address that lag. Both Nebraska Advantage and the ImagiNE Act allow “pooling,” which means that part-time employees can be grouped together and counted as a full time employee — or “full time equivalent” (FTE). As a result, neither program can be guaranteed to induce the creation of only high-quality jobs with benefits.

“Nebraska’s economic development future cannot be based on growth that generates jobs of any kind,” the study said, “but rather growth that emphasized high quality jobs.”[11]

While the ImagiNE Act has some elements that improve upon prior programs in this respect, including a health insurance requirement for full time workers, it nonetheless fails to ensure the jobs being incented are targeted toward companies most likely to positively impact Nebraska’s economic growth.

ImagiNE Act ignores recommendations for best practices

In a series of recommendations for future incentives programs put together for the Legislature’s Economic Development Task Force, the Center on Regional Economic Competitiveness recommended Nebraska ensure its incentives programs: target high-impact businesses; maximize value for companies and the state; are responsive to economic conditions; and protect the state budget. LB 720 with AM 1614 doesn’t follow these recommendations. It makes some strides in the right direction as compared to Nebraska Advantage, such as the use of a minimum rather than average wage. However, a family of four that earns $41,000 a year, which is minimum wage allowed under LB 720, would qualify for reduced-priced lunch[12] and SCHIP benefits.[13]

Ways to make LB 720 better

There are several ways the bill could be improved. The use of caps can help limit the measure’s potential impact on the state budget. Structuring the program as an appropriation rather than a credit would help ensure predictability and regular approval by the Legislature.[14] Giving the Department of Economic Development more discretion over the program could help ensure incentives are targeted to high-impact businesses that likely would not invest but for an incentive. LB 720’s wage thresholds could be increased further and participating companies could be required to provide health insurance for part-time employees as well as full-time workers, as well as other type of benefits such as paid leave.

Conclusion

We recognize that tax incentives are an important economic development tool. Research finds, however, that tax incentives do not pay for themselves and so there is good reason to ensure that Nebraska’s tax incentives are not only inducing the intended economic activity, but are also more cost-effective than other policy options. LB 720 doesn’t contain sufficient measures to do this. Diverting revenue to a program that may not do much to create growth could result in the state making significant cuts to education and other services proven to strengthen both the workforce and the economy. As such, Nebraska would be best served by lawmakers refraining from enacting the ImagiNE Act.

Download a printable version of this analysis.

_________________________________________________________

[1] Bartik, Timothy J. “A New Panel Database on Business Incentives for Economic Development Offered by State and Local Governments in the United States,” 2017, p. 4, https://research.upjohn.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1228&context=reports (accessed May 12, 2019).

[2] Id.

[3] Russell Hubbard, “Nebraska passed corporate incentive laws in 1980s to keep ConAgra in Omaha,” The Omaha World-Herald, September 21, 2015, https://www.omaha.com/money/nebraska-passed-corporate-incentive-laws-in-s-to-keep-conagra/article_9b3da9d0-5f4d-11e5-9496-1ff4bded7dcb.html (accessed May 12, 2019).

[4] Nebraska Department of Revenue, “Nebraska Tax Incentives: 2017 Annual Report to the Nebraska Legislature,” July 13, 2018, http://www.revenue.nebraska.gov/incentiv/annrep/17an_rep/2017_Nebraska_Tax_Incentives.pdf (accessed May 12, 2019).

[5] Id.

[6] Id.

[7] Nebraska Legislature, “LB 720, Fiscal Note,” March 1, 2019, https://nebraskalegislature.gov/FloorDocs/106/PDF/FN/LB720_20190305-133451.pdf (accessed May 12, 2019).

[8] W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, “’But For’ Percentages for Economic Development Incentives: What percentage estimates are plausible based on the research literature?,” https://research.upjohn.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1307&context=up_workingpapers (accessed May 10, 2019).

[9] W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, “Improving Economic Development Incentives,” https://www.google.com/url?q=https://research.upjohn.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article%3D1000%26context%3Dup_policybriefs&sa=D&ust=1557600976537000&usg=AFQjCNHYwId8DvwNZPBlXVhKkTYoFrPVjg (accessed May 11, 2019).

[10] W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, “A New Panel Database on Business Incentives for Economic Development Offered by State and Local Governments in the United States,” (Appendices F3), February 2017, http://research.upjohn.org/reports/225/ (accessed May 12, 2019).

[11] SRI International, “Nebraska’s Next Economy,” http://neded.org/files/govsummit/Nebraskas_Next_Economy_Analysis_and_Recommendations_web.pdf (accessed May 10, 2019).

[12] United States Department of Agriculture: Food and Nutrition Service, “Child Nutrition Programs: Income Eligibility Guidelines,” May 2018, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/05/08/2018-09679/child-nutrition-programs-income-eligibility-guidelines.

[13] Benefits.gov, Nebraska Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), https://www.benefits.gov/benefit/1607.

[14] Pew Charitable Trusts identifies the fact that Minnesota’s Job Creation Fund is funded by an “upfront state appropriations” as a strength. See Josh Goodman, “Pew Charitable Trusts Incentive Program Memo,” October 2018.