Policy brief – Amid budget woes, plan calls for tax cuts for the wealthy

LB 461, the tax-cut package put forth by the Revenue Committee, is first and foremost an income tax cut for wealthy Nebraskans and the proposal does little to truly address property tax relief. In fact, LB 461 is fundamentally flawed in a way that makes it more likely to exacerbate, not help, Nebraska’s reliance on property taxes to fund K-12 education. Furthermore, some Nebraskans would actually pay more in overall taxes under LB 461.

LB 461’s tax changes

Starting in 2018, LB 461 would replace the assessment method of agricultural land from market value to income-capacity, cap the annual aggregate growth of agricultural land valuation and dictate that agricultural use value must fall between 55 percent and 65 percent of actual value. Starting in 2019, LB 461 would cut the top corporate income tax rate and collapse the first two personal income tax brackets. At this time, the bill also would phase out the personal exemption credit for high income earners, introduce a new credit for some low-income earners, slightly increase the earned income tax credit, and eliminate the Nebraska Job Creation and Mainstreet Revitalization tax credit and the New Markets Job Growth tax credit. Starting in 2020, LB 461 would phase in cuts to the top personal and corporate income tax rates when projected revenue growth exceeds 3.5 percent and 4 percent respectively. The personal and corporate income tax rate cuts would occur incrementally until the top income tax rates are reduced to 5.99 percent. Data provided to the Department of Revenue show that when fully implemented, LB 461 would reduce state revenue by $458 million annually.

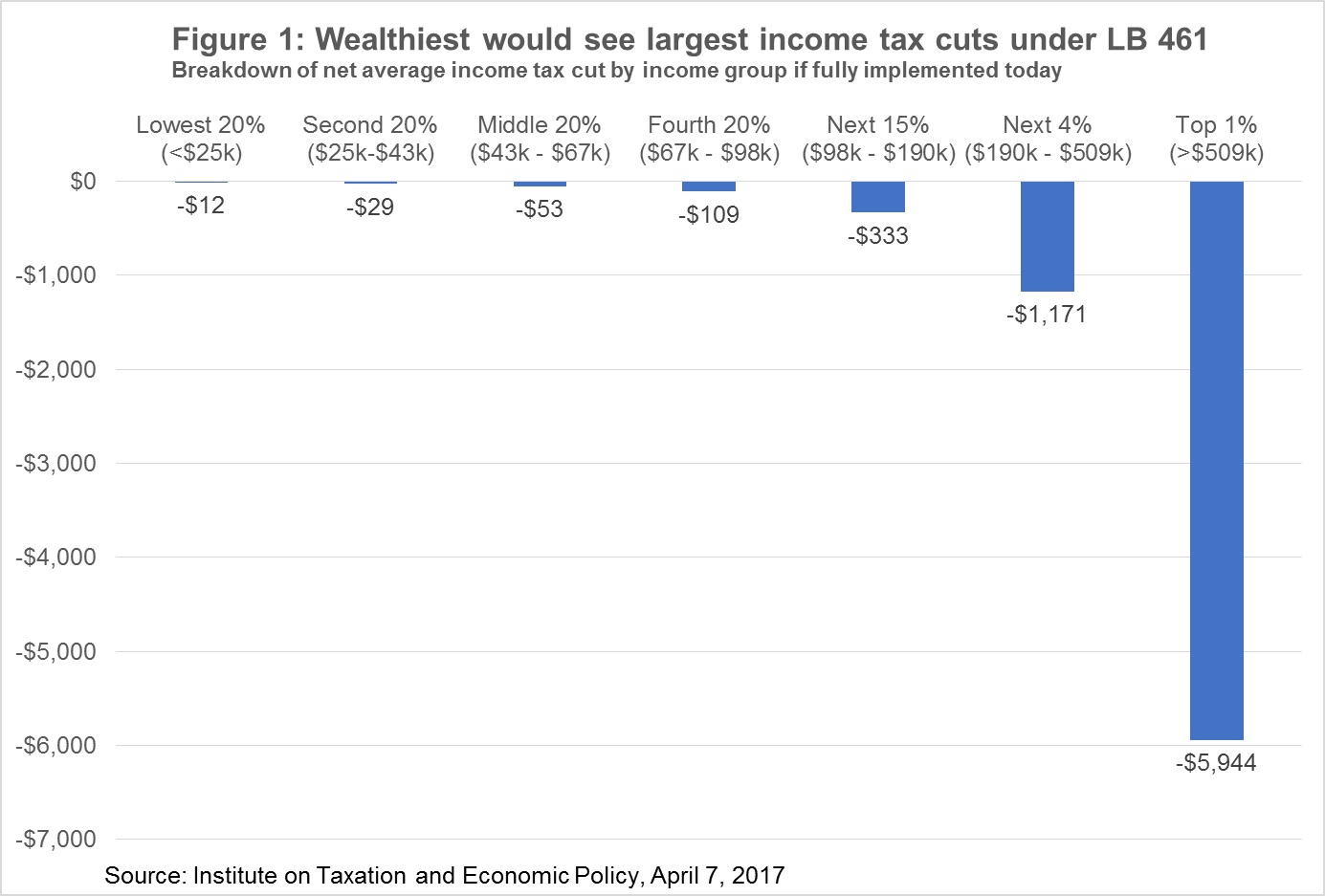

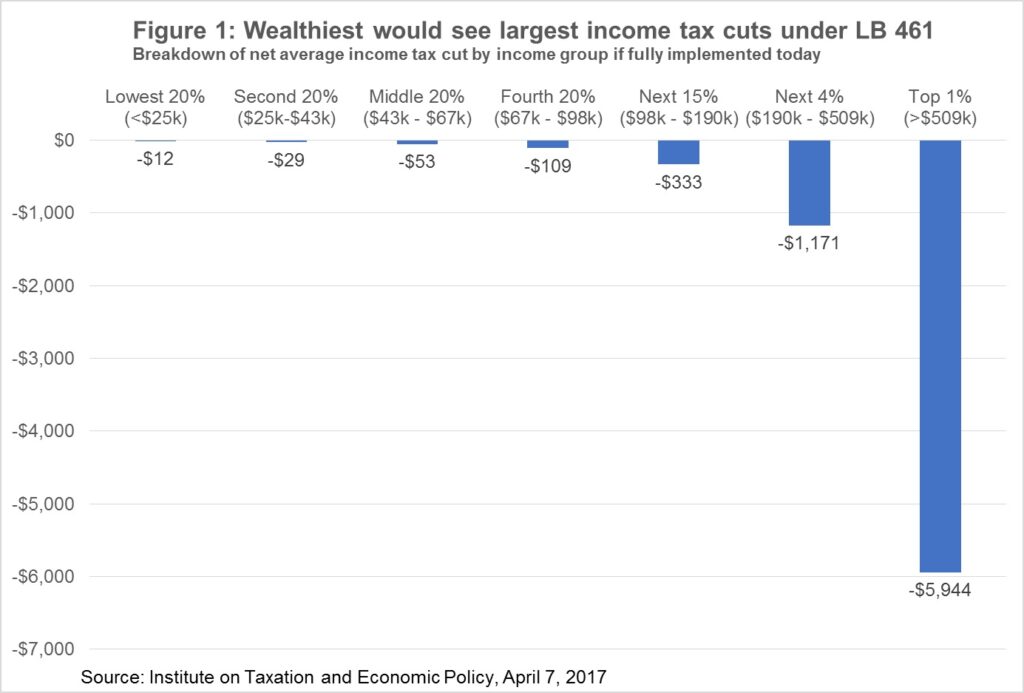

Wealthiest get largest income tax cuts, some would see income tax increases

Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) data (Figure 1) show that if LB 461 were fully implemented today, a Nebraskan in the top 1 percent of incomes would receive an average income tax cut of about $5,944 a year; a middle-income earner would receive about $53 annually on average; and the lowest-earning taxpayer would, on average, receive a $12 income tax cut. About 79 percent of LB 461’s income tax cut would go to the highest-earning 20 percent of Nebraskans with annual incomes greater than $98,000. About 30 percent of LB 461’s income tax cut would go the wealthiest 1 percent of Nebraskans, who on average earn about $1.6 million annually.[1] Also, because of the collapsing of some tax brackets and changes to tax credits, some Nebraskans would actually see income tax increases under LB 461.

Large chunk of tax cut would leave state

About 37 percent of LB 461’s income tax cuts would leave the state each year as the federal government would collect 13 percent more from Nebraskans who would have less to write off on their federal tax returns, and about 24 percent of the income tax cut would go to non-residents who own stock in multi-state companies that do business in Nebraska.

Revenue triggers are not sound tax policy

LB 461 uses income-tax cut triggers based on projected revenue growth – not actual revenue growth. As a result, income tax cuts will be triggered as revenues increase following an economic downturn or when revenue projections are too optimistic. LB 461’s triggers, had they been in place since the early 2000s, would have caused tax cuts amid the recession of the early 2000’s, during “The Great Recession” and another last year following overly optimistic revenue forecasts. Tax cuts following recessions would have depleted the state of revenue needed to replenish reserves used during the downturn. Tax cuts based on overly optimistic projections can intensify unexpected shortfalls and necessitate larger cuts to schools and other services or steeper increases in other taxes. Revenue triggers also set tax cuts on autopilot based on arbitrary levels and don’t allow lawmakers to respond to state needs. In 2016, a tax cut trigger in Oklahoma caused an income tax cut just as oil prices plummeted. This contributed to an ongoing budget crisis that just saw the state’s bond rating decreased due to “revenue failure.”[2]

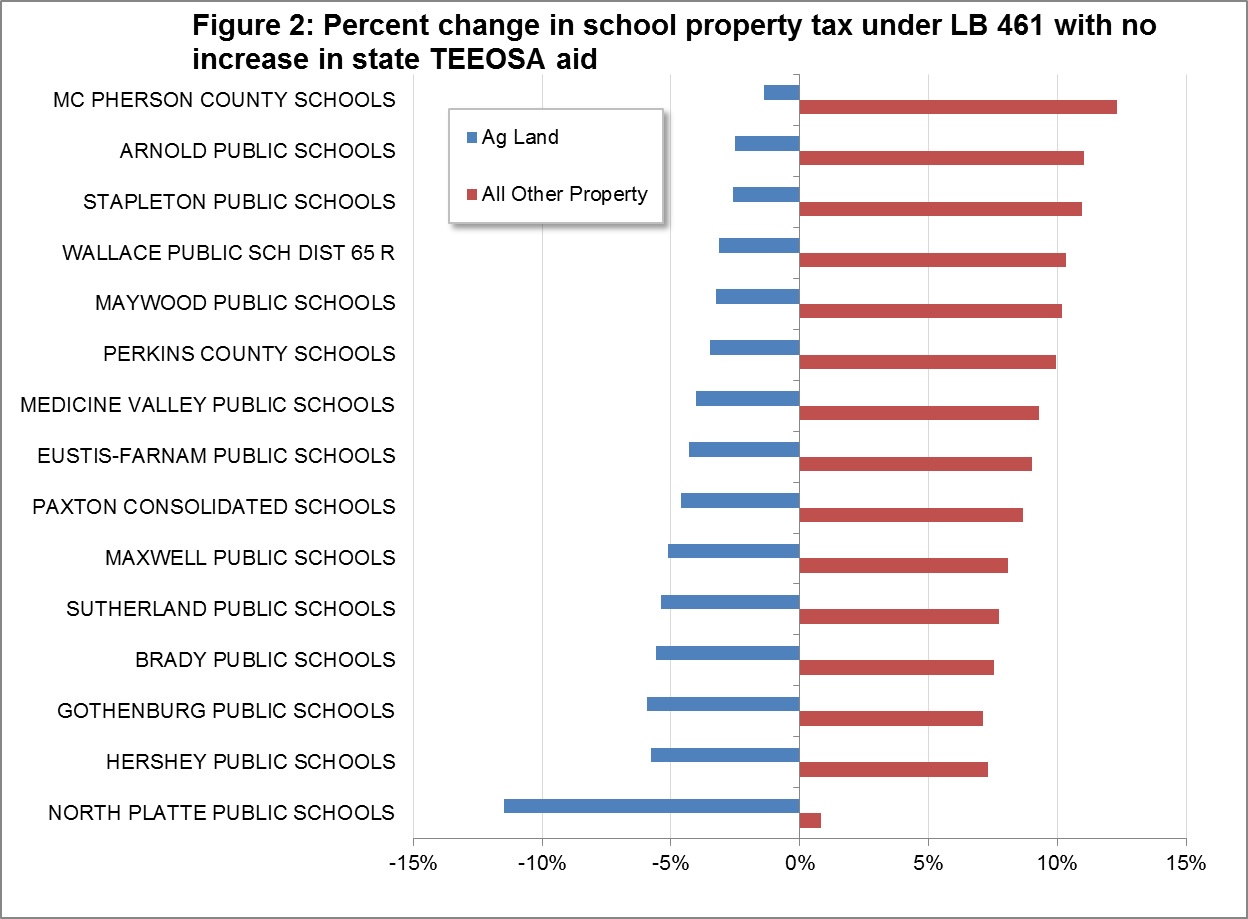

Property-tax changes would cause some to pay more in overall taxes

While the intent of LB 461’s property tax measures is to help the agricultural community, the largest benefits would not go to the most rural parts of Nebraska, but rather to farmers and ranchers near urban areas. This is because the property taxes in urban areas can be shifted and shared with relatively large numbers of nearby business and residential property owners. Such tax shifts cannot occur to the same extent in more rural areas where there are not as many businesses and residential property owners. This means those communities with agricultural land must make up the lost revenue either by levy increases – which would wipe out much of the tax cut from lowering valuations – or by cuts to education, roads and other local services. Furthermore, property tax increases caused by levy increases and tax shifts would more than offset income tax reductions in some cases, leading some Nebraskans to pay more in overall taxes under LB 461.

Lincoln County example

By comparing the school districts in Lincoln County, we are able to see the disparate impact that reduced agricultural land valuation would have – due to shifting of the property tax responsibility.[3] Agricultural land owners in the North Platte School District, where property taxes can be shifted and shared with relatively large amounts of commercial and residential properties, would have seen their property taxes reduced by an average of about 12 percent while taxes on other property types would have increased less than 1 percent on average. In the nearby McPherson County School District, where there is relatively little residential and business property, property taxes on agricultural land would have decreased only 1.4 percent on average and all other property owners would have seen their property taxes increase by an average of 12.3 percent (Figure 2).

Fundamental flaw causes LB 461 to work against itself

By reducing agricultural land valuation, LB 461 would increase the demand for state K-12 aid, but this a fundamental flaw with the measure as the income tax cuts called for in the bill will reduce revenue needed to fund the increase in state school aid. These two ideas are not compatible and would result in higher property taxes and/or significant cuts to K-12 funding. Furthermore, the increase in state school aid would not kick in until FY20, a year after the loss of valuation impacts school district revenue. The reduction in agricultural land valuation would have caused a $141 million shortfall for local governments had it been in effect in FY17. Also, given that the current level of aid called for in our school finance formula is not fully funded in the Legislature’s current budget proposal, it is questionable whether the increase in K-12 aid called for in LB 461 would be funded.

Conclusion

As Nebraska faces a budget shortfall, which a U.S. Government Accountability Office report shows could be the start of a 40-plus year run of budget gaps, it makes little fiscal sense to implement risky measures that reduce revenue further. Furthermore, flaws within LB 461 mean it very well could worsen some issues it was intended to solve. Nebraska and its residents would be best served if lawmakers reject LB 461.

Download a printable PDF of this analysis.

[1] The average tax changes reflected here include the deductibility of state income taxes on the federal return, sometimes called the “federal offset.”

[2] The Associated Press, “S&P lowers Oklahoma’s bond rating amid revenue failure,” downloaded from https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/oklahoma/articles/2017-03-01/s-p-lowers-oklahomas-bond-rating-amid-revenue-failure, on April 13, 2017.

[3] This analysis assumes that LB 461 as well as the changes to the TEEOSA formula in LB 959 and LB 1067 from last session were in place in this year(FY17). It also assumes that local governments raise their levies commensurately to recoup the lost revenue that results from the reduced ag land valuation. Data Source: Nebraska Department of Revenue data provided to the Revenue Committee, April 3, 2017.